Review: Numbers Do Lie by Impact Index and Aakash Chopra

A new book that validates a few longstanding beliefs of cricket aficionados gives credit where it’s due and is an ode to the unsung hero

Are cold numbers and context-free statistics such as runs or number of wickets enough to do justice to the sporting legacy of a champion? The number of times an MS Dhoni or a VVS Laxman stood among the ruins and helped their team bounce back from a middle-order collapse doesn’t always find reflection in the record books. If you are one of those who think Rahul ‘The Wall’ Dravid didn’t get the accolades that he deserved, or that Madan Lal’s tournament-defining performances in the Prudential World Cup of 1983 got overshadowed by the flamboyance of a Kapil Dev or a Sandeep Patil, you are not alone.

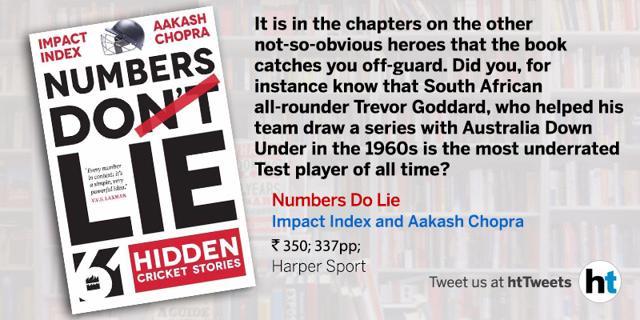

Numbers do lie: 61 hidden cricket stories, Impact Index by Aakash Chopra revisits the record books to measure cricket statistics through the prism of match situations.

Created by filmmaker and writer Jaideep Verma in 2009, the Impact Index is based on a simple premise –accounting for every cricket performance first within the context of its match. And after that, the series or tournament the match is from.

“The tragedy of the cricket world is that people pay attention to the timing of the shot more than the timing of the performance,” says Verma in the introduction. The index appears to be an attempt to fight this irony.

In the process, the book validates a few beliefs that cricket aficionados have entertained for a long time. But it also throws up a few surprises that are an ode to the unsung hero, to give credit that has long been due. On the obvious side, you have chapters affirming how Rahul Dravid is India’s highest impact Test batsman; that AB de Villiers is the most dominating batsman of the modern era; Ravichandran Ashwin well on his way to becoming the highest impact player in Test history or that Virat Kohli was the batsman to absorb the most pressure for India in the 2011 World Cup…

It is in the chapters on the other not-so-obvious heroes that the book catches you off-guard. Did you, for instance know that South African all-rounder Trevor Goddard, who helped his team draw a series with Australia Down Under in the 1960s is the most underrated Test player of all time? Or for that matter, the highest impact player in Test history is none other than Aussie left-arm pace great Alan Davidson? Goddard is rated so highly by the Impact Index owing to his low failure rate of 7 per cent, the fourth lowest in history (for those who played at least 40 Tests) after MS Dhoni, Adam Gilchrist and Jim Laker. His ability to restrict the opposition also made him the fourth highest Economy impact player of all time behind Lance Gibbs, Glenn McGrath and Muttiah Muralitharan. “There’s limited information about South African cricket before the apartheid era and whatever little that is there, it’s about Graeme Pollock or Barry Richards. It’s a travesty we don’t know more such stories…” writes Chopra about this Protean hero.

Davidson’s story wasn’t exactly unsung. The Aussie media of the 1950s and the 1960s has showered fulsome praise on the left-arm pace bowler, which would inspire the likes of Wasim Akram. But to call him the highest impact Test player in history requires an understanding of how he spearheaded the Aussie attack against some of the greatest names to wield the willow: Englishmen of the calibre of Len Hutton, Denis Compton and Peter May, along with Sir Garfield Sobers at the height of his powers apart from the three Caribbean Ws: Frank Worrell, Everton Weekes and Clyde Walcott. After the exit of Bradman in 1948, Australia had lost their Test supremacy to England in 1953, as Len Hutton and then Peter May led England to their most prolific phase in Test history when they didn’t lose even one of their 14 Test series including three Ashes triumphs. In 1958-59, Australia regained their glory with a 4-0 victory in Australia, riding high on Davidson’t high-impact performances.

But my favourite story about an unsung hero who features in the book is about Sadagoppan Ramesh. An elegant Southpaw opening batsman, those who remember Ramesh’s meteor like appearance on the international scene in the late 1990s recall his languid grace and his reputation as a touch player. In the second Test match of his career, opening the batting against Pakistan at the Ferozeshah Kotla, Ramesh made 60 out of India’s 252 with only captain Azharuddin (67) playing a significant hand with him and went on to top score in the second innings with 96. Then came Anil Kumble’s 10/10 and nobody bothered to appluad Ramesh or Harbhajan Singh who bowled brilliantly but went wicketless. Four matches later, playing against New Zealand at Kanpur’s Green Park stadium he would put on a 162-run opening partnership with Devang Gandhi (remember him, domestic cricket’s forgotten Gandhi?). After such a promising start, owing to a mix of indifferent form and fitness, Ramesh was dropped from international cricket at the ripe age of 26. Although he managed to play just 19 Tests before walking back to oblivion, he is rated the third highest Indian Impact Test batsman after Cheteshwar Pujara and Rahul Dravid.

In another chapter, the authors say no batsman in the world absorbed more pressure in Test cricket than Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi. Absorbing observation, or a mere sweeping statement? The chapter elaborates upon how on innumerable occasions Tiger Pataudi soaked in the pressure of wickets falling around him better than a Peter May, an Andy Flower, a Brian Lara, an Angelo Mathews or a Younis Khan. He displayed that standing-on-the-burning-deck ability that separates the men from the boys.

Read more: You will always be my captain, emotional Virat Kohli tells Mahendra Singh Dhoni

At another time, the book asserts that five of Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar’s six series defining knocks in Tests came as a support act: when someone either took the lead (Leeds, 2002; Chennai, 2008) or scored more than him (Colombo, 2010; Mohali, 2010) or contributed with him (Chennai, 1998). It is with assertions such as these, which suggest cricket’s God was mortal and batted best as a support act that the book shines in its ability to view the gentleman’s game beyond meaningless numbers.

Can placing records in a context stand the test of time and emerge as an alternative way to assess cricketers? That is something which will have to stand the test of time. I feel the Impact Index should give greater weightage to another filter which helps you contextualise Test performances: pitch conditions in inhospitable terrain, read Virat Kohli failing in England as opposed to Steve Smith flaying Indian spinners here. I also feel that the book will find greater favour with the tribe of number crunchers -- and these abound among cricket fanatics in the country -- than the lay reader who may find it complex and may have to plough through the guide to understanding the index. Still, I enjoyed this alternative and refreshing take on statistics that may prove meaningless without a context. Navjot Sidhu, India’s most underrated batsman in both Tests and ODI cricket according to the authors, may have put it this way: Guru! Cricket statistics are like mini-skirts, they show more than they reveal!