Review: Love, War and Other Longings; Essays on Cinema in Pakistan

A collection of essays on cinema in Pakistan edited by Vazira Zamindar and Asad Ali includes pieces on its troubled history, its iconic cinema halls, and the impact of the blockbuster Maula Jatt

One of my most memorable cinematic experiences came early in life when, as a seven year old, I first visited a drive-in cinema in Karachi. My cousins there, not very well off, hired taxis and cars and took us to one more than once. The magic of a giant screen in open air, of families sitting in cars enjoying a picnic while watching a film, alongside its beaches and joyrides at Clifton, made Karachi a particularly unforgettable experience. I remember that one of those films starred Nadeem and Shabnam, who, along with Mohammed Ali and Zeba, were the star pair that then dominated the Pakistani film industry. My other memory of Pakistani films is an afternoon at Oxford 25 years ago where a bunch of us Indians and Pakistanis watched Sholay and Maula Jatt back to back, courtesy Osama Siddique, now a famous Lahori writer, and had many laughs together. The recent humongous success of the Fawad Khan-starrer Maula Jatt redux seems to be Sultan Rahi’s (the star of the original film made in 1979) revenge against us for laughing at him that afternoon. Further, before I get to the book, here is another conundrum. We are all fans of Pakistani television serials, which became familiar to us with the arrival of the VHS and which brought Dhoop Kinare and Tanhaiyan, along with Moin Akhtar and Umar Sharif to our homes. Their continuing popularity even recently impelled Zee, one of India’s largest networks, to dedicate an entire channel to them. So why does a people who so excel in television, and generate such progressive content, consistently fail in cinema? Or do they? 2022 was a great year for Pakistani cinema. Apart from the worldwide success of The Legend of Maula Jatt, another film won an award at Cannes, an unprecedented feat. The recent revival of the Pakistani film industry, as well as its changing fortunes down the decades is the subject of this marvellous collection of essays which emerged out of two film festivals at the Universities of Harvard and Brown in the US.

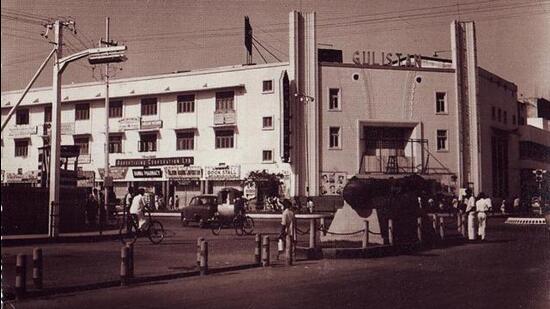

Yes, there was once a thriving culture of making and watching films in Pakistan. At its height in the 1960s and 1970s there were more than a thousand cinema halls in Pakistan, and hundreds of films were produced every year, mostly in Urdu, which rather resembled the socials produced in Bombay, an industry which has, understandably, ever haunted Pakistani cinema. Until 1947, Lahore was one of the major centres of film production in India and Manto, who forms the subject of an incisive essay by niece Ayesha Jalal in this collection, has written about his struggles there after he migrated to Pakistan. Much of the Bombay film industry was and remains dominated by people of Pakistani Punjabi origin, including the triumvirate of Dilip-Dev-Raj, the Kapoors of several hues, the Chopras, the Sagars et al. Indian films found a steady release in Pakistan until the 1965 war. The ban imposed thereafter further propelled the Pakistani film industry.

This highly readable collection comprises many different kinds of essays. One of the editors Vazira Zamindar, is the author of an outstanding monograph on Partition (http://cup.columbia.edu/book/the-long-partition-and-the-making-of-modern-south-asia/9780231138475 ) and took the lead in organising the festivals that produced this volume. She contributes two wonderful essays including one on an incredible one-man film archive run by Guddu Khan in his bare two rooms in Karachi. This is a rather different effort from another one man archive on music which is globally celebrated – the much more resourceful one put together by Lutfullah Khan in Karachi too. Iftikhar Dadi, one of the founders of Karachi pop and a highly distinguished artist and art historian who has lectured extensively in India, writes about the aesthetics of Pakistani cinema and its interactions with art and the cinematic limitations of its TV industry, despite its progressivism. The journalist Fahad Naveed puts together a poignant photo essay about cinema halls. There is a delightful photo essay by Bani Abidi, one of the pioneers of video art in Pakistan, about the burnt reels of Nishat cinema after it was attacked by a mob. In a brilliant essay on death and hauntings and rebirths, Meenu Gaur – one of the great anomalies of subcontinental cinema, a Calcutta born, Delhi trained filmmaker who makes breakthrough films set in Pakistan – and Asad Ali write about the contradictions surrounding Maula Jatt, which ran continuously for 216 weeks until martial law authorities took it down.

In their introduction the editors spell out the conventional periodization of Pakistani cinema as follows:

“one can speak of (a) Karachi and the Urdu Social until the mid-1970s, (b) the emergence of Lollywood from roughly the mid-1970s to the late 1990s, and (c) a new constellation once again centred on Karachi, from roughly 2013 onwards.”

It turns out that the cult status of Maula Jatt marks a cleavage between two Karachi-dominated epochs. The original Maula Jatt was released in 1978 and the story of its success and how its producer fought the censors is the centrepiece of this history. Sultan Rahi, its protagonist, became a one-man industry and spawned two decades of violence and revenge-based films that were too risqué for the middle classes who abandoned the cinema. Sultan Rahi’s angry young man persona brought a new kind of angst and irreverence to the screen, in common with the rise of the anti-hero around the world in that decade. The rise of the Punjabi film industry and Lahore’s dominance coincided with the Zia years and its intense censorship when cinema became an object of condemnation and censure. The authorities tried to ban Maula Jatt but they were too late.

“The story in which the hero, Maula Jatt, delivers justice to the doorstep of the poor had already become the stuff of legends. Nearly 25 years later, the imagery of Maula Jatt remains deeply engraved in Pakistani pop culture iconography. The film is also well-remembered for setting a trend in movie making that would not entice the urban, educated audiences. A sea of films would copy its blueprint for decades, and as Pakistani cinema became violent, alienating skilled talent and regular family audiences, so did Pakistani society. Quality declined, and so did the Pakistani film industry.”

A year after we watched Maula Jatt at Oxford, Sultan Rahi was assassinated for reasons that still remain unknown. Official news reports claim it was a robbery; others believe the cause to have been a land dispute; yet others believe he was killed by religious bigots because of his imminent plans to reconvert to the religion of his birth, ie Christianity.

“This sudden death also more or less coincided with another untimely death, that of the Pakistani film industry itself. While several factors were responsible for the decline of the industry — including the creation of Bangladesh and the consequent loss of film personnel and market territory, the military dictatorship of General Zia and its oppressive censorship policies, and the proliferation of VHS — Sultan Rahi’s passing most definitely heralded the end of an era, after which Lollywood more or less struggled with its own extinction.”

Yet, Pakistani cinema also has an ideological battle to fight for legitimacy, a battle that cinema in India had appeared to conquer before recent ideological assaults on Bollywood. In 2012, a series of attacks by rioters resulted in six cinemas being burnt in Karachi and Peshawar. Ali Nobil Ahmad, one of its foremost scholars of cinema has gone so far as to call Pakistan “one of most cinephobic nations on earth.” Discussing the classic text Pakistan Cinema 1947–1997 by Mushtaq Gazdar, Ahmed argues that this disowning of Lollywood (the Lahore-based film industry) and its culture by the state and society is not a result of the Islamization of the Zia years, but was, in fact, the official position of the early Pakistani state, which viewed cinema as “sinful”. As a cinema owner states, “Our biggest misfortune is that we Pakistanis are making films in a country in which watching films is seen as a crime. People ask us why our industry is not prospering, and I always tell them that this industry cannot prosper until film and filmmakers are given their due respect. A nation that addresses its musicians as marasi, film personnel as kanjar, and film heroines as gashti (ie prostitute) — how can the industry of that country prosper?”

While there was a steady decline in the number of films being produced annually from 1989 onwards, it became especially acute after 2003, when, despite 50 films being released, there were fewer blockbusters. The slump continued until it reached a production low of 23 films in 2012, which coincidentally was the year when religio-political protestors attacked and burned five cinemas in Karachi. Hence 2012 is widely perceived as the nadir for film in Pakistan. As many have noted, the following year marked a revival in both the number of productions (up to 37) and box office success. What is notable, especially since 2015, is the decline in the number of Punjabi films, and the increasing production and dominance of Urdu. Karachi has once again emerged as the capital of the Pakistani film industry where television giants such as Geo, Hum and ARY are based and it is the talent and financial muscle of its TV industry that is now helping revive its cinema. This revival is also linked to the decision by General Parvez Musharraf to re-allow the screening of Indian films and the liberalisation of the TV industry that he promoted. One of the early outcomes of this was Khuda Kay Liye, a film which enjoyed great success upon this theatrical release in India. Another recent success was Zinda Bhag, directed by Meenu Gaur mentioned above, which Iftikhar Dadi discusses in detail in this book. In 2015, a war film actually called Waar reversed the conventional Bollywood gaze and projected India as a terrorist disrupter in Pakistan and enjoyed huge success. Its Director Bilal Lashari went on to remake Maula Jatt starring Fawad Khan which has, once again, become the greatest hit of Pakistani cinema. Further, Joyland by Karachi-based Saim Sadiq became the first Pakistani film to win the Jury Prize of the Un Certain Regard section at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival.

The conventional view in Pakistan laments the decline of bourgeois national Urdu cinema’s golden age, which was eclipsed by the dark age of bawdy and violent Punjabi cinema. This also resulted in a shift in audiences from the urban middle classes to the working class, until the last decade when new multiplexes and new policies — such as not allowing stags to enter alone — has resulted in a new gentrification. Yet, as Faiz’ granddaughter Mira Hashmi remembers here, the experience of single screen cinema halls remains unparalleled. She refers to the cinema of the time — that is, of the late 1970s and early 1980s — as the “great leveller”. English speaking upper-middle-class people, rickshaw drivers, factory workers, all would see the same film in the same hall, “pay the same amount of money for the same snacks, and immerse themselves in the same cultural conversations.” It was the same in India too, until the 1980s, a decade that comes in for universal flak here. Yet, the cinema of that time depicted the poor and their lack of faith in the system, and was watched by the poor. At the same time, as the poor and the working classes disappeared from the screen — one would be hard pressed to remember a working class hero in any film thereafter — they also simultaneously disappeared from the cinema halls in India. Both became more purely bourgeois. And still, if one were to compile a list of the best Indian films of the 1980s, it is possible that it might remain unsurpassed by all the best films made in India in the subsequent three decades. Just off the cuff let me start listing, outside of the parallel cinema, Masoom, Ijazat, Mr India, Parinda, Karz, Sadma, Khoobsurat, Bazar, Naram Garam, Umrao Jaan, Saransh, and I am not even mentioning some of the great Amitabh Bachhcan hits such as Namak Halal, Yarana, Aakhri Rasta or the arthouse films such as Katha, Chasme Buddoor, Ardh Satya, Saleem Langde Pe Mat Ro, Sparsh and innumerable others. The range and quality of these films has remained unsurpassed in my opinion.

While cinema remains popular it has begun to see huge dents from digital platforms and is no longer the mass phenomenon that it once was in South Asia. Still, the revival of the Pakistani film industry, and conversations around it alert us not just to the commonalities we share but also that our post-colonial trajectories, despite our different political experiences, may not be so dissimilar after all. One must remember that the entitled bourgeoisie in all of South Asia aspire to and consider themselves to be organically linked to the universal Enlightenment values of Europe, and, in fact, it is Maula Jatt who challenges this hegemony.

Mahmood Farooqui is best known for reviving Dastangoi, the lost Art of Urdu storytelling.